Lindbergh Kidnapping

Ape-Man

Fatty Arbuckle

The Black Dahlia

The Brinks Job

Lana Turner

The Great Train Robbery

Richard Speck

Tate Murders

Patty Hearst

Son of Sam

John Wayne Gacy

Ted Bundy

Art Heist

Jeffrey Dahmer

O.J. Simpson

Barings Bank

The Unabomber

JonBenet Ramsey

Versace Killings

Mary Kay Letourneau

Columbine

Andrea Yates

The Scream

Lindbergh Kidnapping

Lindbergh Kidnapping

The Crime

.jpg)

On a cold rainy night, March 1, 1932, in the remote rural area near Hopewell, New Jersey, Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr., twenty months old, was kidnapped. Sometime between 8:00 p.m., when his nurse, Betty Gow, checked on the sleeping baby, and 10:00 p.m., when she once again checked on him before retiring for the night, "The Eaglet" (as the newspapers called him) had been removed from his crib.

The only remembered event that indicated that something had gone amiss was earlier, about 9:00 p.m., while the Lindberghs were sitting in the living room. Col. Lindbergh had heard a noise that sounded as if an orange crate had fallen off a chair in the kitchen.

.jpg)

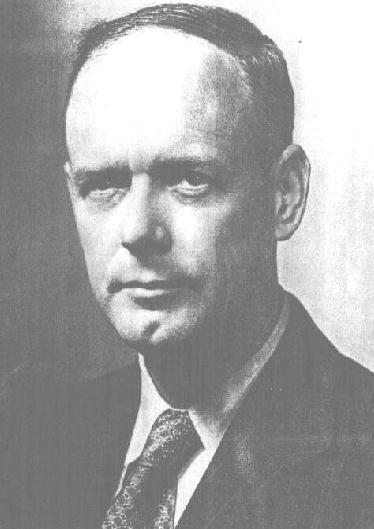

At 10:25 p.m., Ollie Whately, the Lindbergh caretaker, called the Hopewell Police, and shortly thereafter Col. Lindbergh called the New Jersey State Police. In the cold dark, Lindbergh hunted for signs of the kidnapper, carrying his Springfield rifle. He could see nothing. A number of State Police officers were on the scene, when around midnight their chief, H. Norman Schwarzkopf, arrived to take command.

The impressions of Col. H. Norman Schwarzkopf are mixed. He was an army officer in World War I. At the age of twenty-six, he was appointed the first head of the New Jersey State Police, which he designed and ran as a military body. The organization was strong on enforcement, but weak on investigation. His "troops" had military ranks and wore quasi-military uniforms. He was the father of 1991 Desert Storm commander H. Norman Schwarzkopf, Jr.

While he was excluded from much of the planning to connect with the kidnappers, and while much of his advice was over-ruled by Lindbergh and his lawyer, Henry Breckinridge, once the Eaglet's body was discovered in early May, he took charge of the investigation. It was clear that he found it difficult to cooperate with the New York City Police, the FBI, and other investigative units. Lindbergh expressed confidence in him, particularly during the unproductive months that followed the discovery of the child's body, during which time the efforts of the State Police were roundly criticized.

The first of the state police to arrive investigated the outside area. They found footprints in the wet ground below the window, but neglected either to measure them or to make plaster casts of them. There were two deep impressions, presumably made by a ladder. Also, a carpenter's chisel was found near the ladder impressions. Less than a hundred yards away, the ladder, in three sections, was discovered, the bottom section —the widest —was broken. Near a small dirt road, there were tire tracks.

.jpg)

By this time, Lindbergh's lawyer and friend, Henry C. Breckinridge, had arrived. The three colonels (Lindbergh, Breckinridge, and Schwarzkopf) went into the nursery with other officers and Cpl. Frank Kelly, the crime scene and fingerprint man.

.jpg)

The case, later described as a travesty, was tried three times, two ending in hung juries, before Arbuckle received an innocent verdict. But the damage had been done to his career. Many refused to believe in his innocence and movie industry executives blacklisted him and warned his friends to stay clear.

No comments:

Post a Comment